Russian Applied Art of the 10th 13th Century

"1 should not forget about the architectonics of a book. Information technology is not enough to create a title page, vignettes, and endplates . . . A good architect is capable of drawing a good plan of the building to be erected, of creating clever combinations, stunning details, and a consummate 'anatomy' of the building . . . The same applies to the book designer, who beginning of all should pay attention . . . to the paper's format, quality, surface, and colour; to the placement of the text on a page" (Alexandre Benois, 1910, quoted in Rosenfeld 2014, 178).

The Neo-Russian Style and the Folk Art Revival

The roots of the and then-chosen Neo-Russian style lie in the revival of Russian peasant crafts in the 1870s, which paralleled similar revivals in the West such as William Morris'due south Craft movement. In Russia, members of the elite and educated classes, mourning the disappearing craftsmanship of the kustar ("peasant handicraftsman"), created workshops in the countryside to encourage villagers to practice traditional crafts instead of moving to the cities to work in factories (Salmond 1996, 1–8).

I of the most of import centers of the kustar revival and the Neo-Russian style was in the Abramtsevo Circle, a neo-romantic group that formed in 1878 around the Abramtsevo estate of the railway entrepreneur Savva Mamontov (1841–1918), whose members collaborated in furniture blueprint, theatrical gear up ornament, costume pattern, compages, embroidery, and volume illustration. Abramtsevo apprentice theatrical productions laid the groundwork for the innovative Russian stage blueprint of the early twentieth century, which became famous in the West thanks to Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Like Diaghilev, Mamontov was a larger-than-life figure with g ambitions; he has been called the "Russian Medici" (Iovleva 2007, 34). Overall, the Abramtsevo Circle influenced several Russian modernist trends, such every bit theatricality, the notion of the overall unity of the artwork, and an emphasis on decorative arts, applied arts, and folk motifs.

Nigh significantly for the history of children's volume design, the Abramtsevo Circle set the phase for the flowering of Russian volume illustration and the incorporation of the Neo-Russian style into children'due south books. While similar to Western Art Nouveau, the Neo-Russian manner was distinct in its integration of medieval Russian civilization and folk traditions. Particularly important in this regard was Viktor Vasnetsov (1848–1926), who was originally associated with the realistic artists' group chosen the Peredvizhniki ("The Wanderers"), just who then laid the background for the Neo-Russian style by integrating motifs from Russian folk art, epics, and fairytales into his works. Another Abramtsevo figure seminal in the evolution of fin-de-siècle book design was the artist Yelena Polenova (1850–98), whose children's volume illustrations comingled realistic traditions with stylized folk-art ornamentation and a sense of the Gesamtkunstwerk: the volume equally an integrated artistic object. (On Abramtsevo overall, and the Neo-Russian way, see Jackson 2007, 37–43; Paston 2014, 59–78; Rosenfeld 2014, 173–78.)

The Emergence of Russian Art Nouveau and Mir Iskusstva ("The World of Art")

Russian Art Nouveau echoed a broader European trend of the tardily nineteenth century, when artists revolted against scientific positivism, traditional realism, and an increasingly industrialized globe. In Western Art Nouveau, this impulse steered artists towards stylized ornament, flattened simplicity, an accent on practical arts and graphic design, and the use of motifs from Japanese art, vernacular folk arts, and organic forms (Greenhalgh 2000b, 6–25; Fahr-Becker 2007, 7–23). Western Fine art Nouveau is known for its ornamental curves, plant arabesques, and "flickering, feathery, flowing linearism" (Fahr-Becker 2007, 13 & sixteen).

As a term, Russian Fine art Nouveau broadly refers to those fin-de-siècle trends in the arts that echoed elements of Western Art Nouveau, rather than to a group that adopted that specific label. In fact, Russians of this era oft only referred to Art Nouveau as "mod style" (based on the French: style moderne or style russe moderne; in Russian: стиль модерн. The British besides used the term "Modernistic Style"; meet Salmond 1996, two–three, and Fahr-Becker 2007, 7). Regardless of the variants in terminology, Russian Art Nouveau shared much with its Western counterparts.

A distinct strand of Russian Art Nouveau emerged towards the end of the nineteenth century, vibrantly embodied by the artistic coterie that termed itself Mir Iskusstva ("The Earth of Art"). The members of this group, often called miriskussniki, emphasized collaboration beyond the arts and became renowned for their achievements in theatrical blueprint and book illustration. In fact, Mir Iskusstva independent two distinct strains: a Westernizing group that embraced both Western Art Nouveau and the more distant eighteenth-century past, and an alternative group focused on Russian folklore and the Neo-Russian style. As we will see, both groups contributed to the flourishing of children'due south book design.

Although Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929) became the eventual leader and organizer of Mir Iskusstva, which he then farther publicized in the West through his famous Ballets Russes, information technology was in the social circles of Alexandre Benois (1870–1960) that the group originated. Benois later recalled that they often met at his firm in St. Petersburg, at the corner of Nikolskaya Street and Ekateringofsky Prospect, equally early on as 1890. Benois was seen as the "pedagogue" and "theoretician" of the group, and influenced many of their activities, such as lectures and musical evenings. They called themselves the "Nevsky Pickwickians," and their group was characterized past both serious intellectual endeavors and "schoolboy humor" (Bowlt 1979, 49–50). Significant influences on their group included Corrupt and Symbolist artists such as Aubrey Beardsley, Arnold Böcklin, and Edvard Munch. Like Walter Crane and other Western artists, the Russian miriskussniki were strongly drawn to Japanese woodblock prints because of their "asymmetrical composition," "respect for empty spaces," and "the articulate beauty of the line" (Fahr-Becker 2007, 9). The Russian linearism also echoes that of their Western counterparts: "The World of Fine art members . . . regarded the line every bit the well-nigh expressive visual element; even in their paintings, the line was the ascendant force" (Petrov 1997, 41).

Their eponymous periodical, Mir iskusstva (1898–1904), published an eclectic range of literary and visual works, including fine art in the Neo-Russian style; verse by the Russian Symbolists; reviews of art, music, and literature; and the works of Western Decadents such every bit Beardsley and Huysmans. The periodical's greatest legacy was its synthetic approach and emphasis on graphic design. (On the Mir Iskusstva grouping overall, see Bowlt 1979 & Petrov 1997. On the periodical, see Kennedy 1999, 63–78.)

The Miriskussniki and Book Design

Both the Mir Iskusstva group and their periodical proved hugely influential, specially in their emphasis on graphic blueprint overall and book analogy in particular. In both Russia and the W in this era, "the book as such became a thing of beauty" (Lemmens & Stommels 2009, 25). Like Walter Crane in England, every bit seen in the previous essay, the miriskussniki stressed the notion of the volume equally an integrated work of art in itself, and created a renaissance in volume pattern, "based on the concept of the book as 1 integral decorative and graphic entity" (Petrov 1997, 120).

Golynets notes that book analogy itself lies intriguingly "on the dividing line between easel painting and applied art" (1981, 9), and equally such it embodies the focus of Mir Iskusstva. "Illustrations now became as important as the text, and the book was created like a work of easel fine art" (Solomatina 2001, thirteen). While the illustrators of the Abramtsevo Circle lay some of the groundwork for the focus on book design, the artists of Mir Iskusstva raised this to a new level: "The children'south book designs of . . . Mir Iskusstva were spectacular achievements in prerevolutionary artistic civilisation." They united "text and illustrations into stunning, integrated wholes" (Rosenfeld 2014, 184).

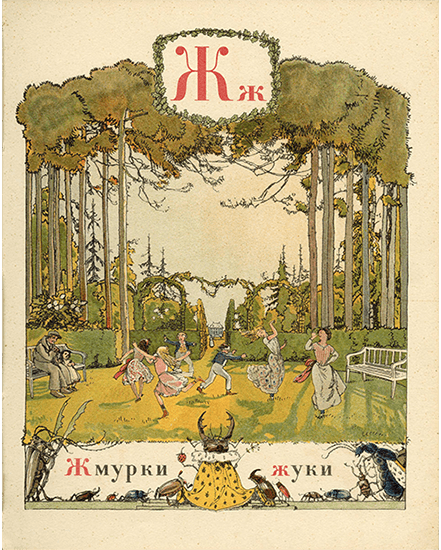

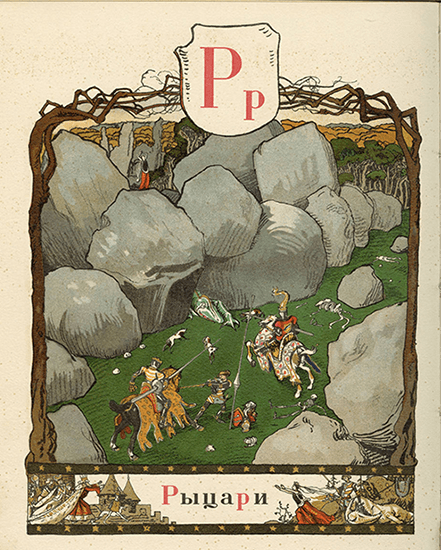

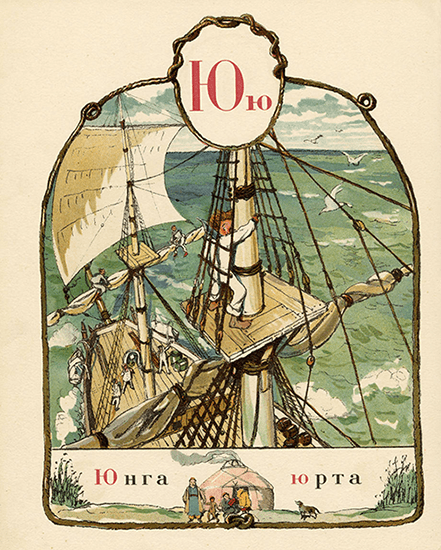

Alphabet in Pictures

In their works for children, the miriskussniki emphasized a stylized world of fairytales, folk motifs, and decorative ornament. 1 of the near outstanding examples is Alphabet in Pictures (Azbuka v kartinakh, 1904) by Alexandre Benois. An oversized, large-format volume (10" x 13"), it devotes a lavishly decorated, full-page color illustration to each letter of the alphabet of the Russian alphabet, including letters that are no longer used due to the Soviet orthographic reforms.

This volume was inspired past and dedicated to Benois'due south own children: his son, who turned three the year the book was finished, and his daughter, who served every bit a model for many of the illustrations (Rosenfeld 2014, 178). It reflects Benois'due south own views on children's books equally a ways of escape into a dreamworld: he later declared that a children'southward book should be "a dream of the distant and audacious," non a "dull, gray . . . bounding main of vulgarity . . . and drunken shoemakers" (Benois 1908; quoted in Hellman 2013, 281). Many critics agree that this book was enormously influential on subsequent children'southward book blueprint: Benois's Alphabet in Pictures "represents a milestone in the career of its creator," and was 1 of "the pioneering examples of Russian children's book illustration" as well equally "a manifesto of the World of Art attitude toward children's volume analogy" (Rosenfeld 2014, 178; Rosenfeld 1999d, 82).

Eighteenth-Century Stargazing

The artists of Mir Iskusstva oftentimes engaged in a nostalgic "poesy of retrospection" (Makovsky 1914, quoted in Golynets 1981, 191). Nevertheless the Westernizing branch of the group, spearheaded by Alexandre Benois, focused not on the Neo-Russian style and folklore of the pre-Petrine era as advocated by the Abramtsevo Circle, merely on more Westernized cultural influences, embodied past Peter the Great's Russia and Louis XIV's Versailles. This "retrospective" style, which delighted in both the Rococo and neoclassical styles of the eighteenth century, distinguished Russian Fine art Nouveau from some of its Western counterparts. Benois in particular "reveled in the sinuous arabesques of Rococo design" (Petrov 1997, 43–44, 95; Kennedy 1999, 63 & 70). His work ofttimes embodies an eighteenth-century sensibility, not only in his paintings, but also in his children'due south book design, as seen on page 10 of Alphabet in Pictures, in which bewigged aristocrats please in stargazing, with the panorama of Saint petersburg and the spire of the Peter-Paul Fortress framing their endeavors.

Theatricality

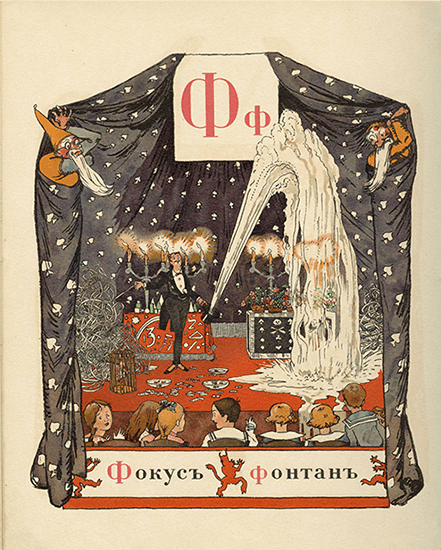

Theatricality played a pregnant role in Russian Art Nouveau overall, and for the oeuvre of Benois in particular. Benois himself said that he worshipped the theater and saw all fine art in terms of "theatricality" (Petrov 1997, 41). Benois later on had a successful career equally a theater designer, creating sets and costumes for operas, ballet, and theatrical productions, and he oftentimes collaborated with Diaghilev (Bowlt 1979, 190–98). His dear of theatricality is well reflected in the pages of Alphabet in Pictures, in which many of the scenes are presented as theatrical events, replete with sinuous curtains and unexpected audience members. On page 24, for case, the alphabetic character "F" is represented past Fokus ("Magic Тrick") and Fontan ("Fountain"); hither Benois depicts a magic show attended by an enthusiastic grouping of children, one of whom is turned towards the viewer, as if to emphasize the theatrical frame. The scene overall is draped by a blackness curtain decorated with white spades, evoking the effect of white stars against a dark, bogus sky. Overall, Alphabet in Pictures "resembles a theater in a volume," every bit critics accept noted, since "the framing of every inset composition is itself theatrical" (Rosenfeld 2014, 180; Weld 2018, 34).

The other side of Mir Iskusstva, heavily influenced by folk fine art and the Neo-Russian manner, was embodied by Ivan Bilibin, as we will meet in the next essay.

More ...

View examples of Bonois's works in the Harer Collection »

Source: https://content.lib.washington.edu/exhibits/russian-childrens-lit/3-artnouveau.html

0 Response to "Russian Applied Art of the 10th 13th Century"

Post a Comment